Soy Sauce Is Finished—Yet It Still Changes

Soy sauce is often described as a finished product.

Its fermentation is complete, its flavor stable,

its character defined.

And yet, in everyday Japanese cooking,

the impression of soy sauce continues to shift—

quietly, without anyone announcing it.

This article is not about which use is better.

It is about noticing that something does change,

even after fermentation is complete.

Rather than evaluating soy sauce by quality or correctness,

this piece looks at a simple phenomenon:

how the same soy sauce behaves differently depending on how it is used.

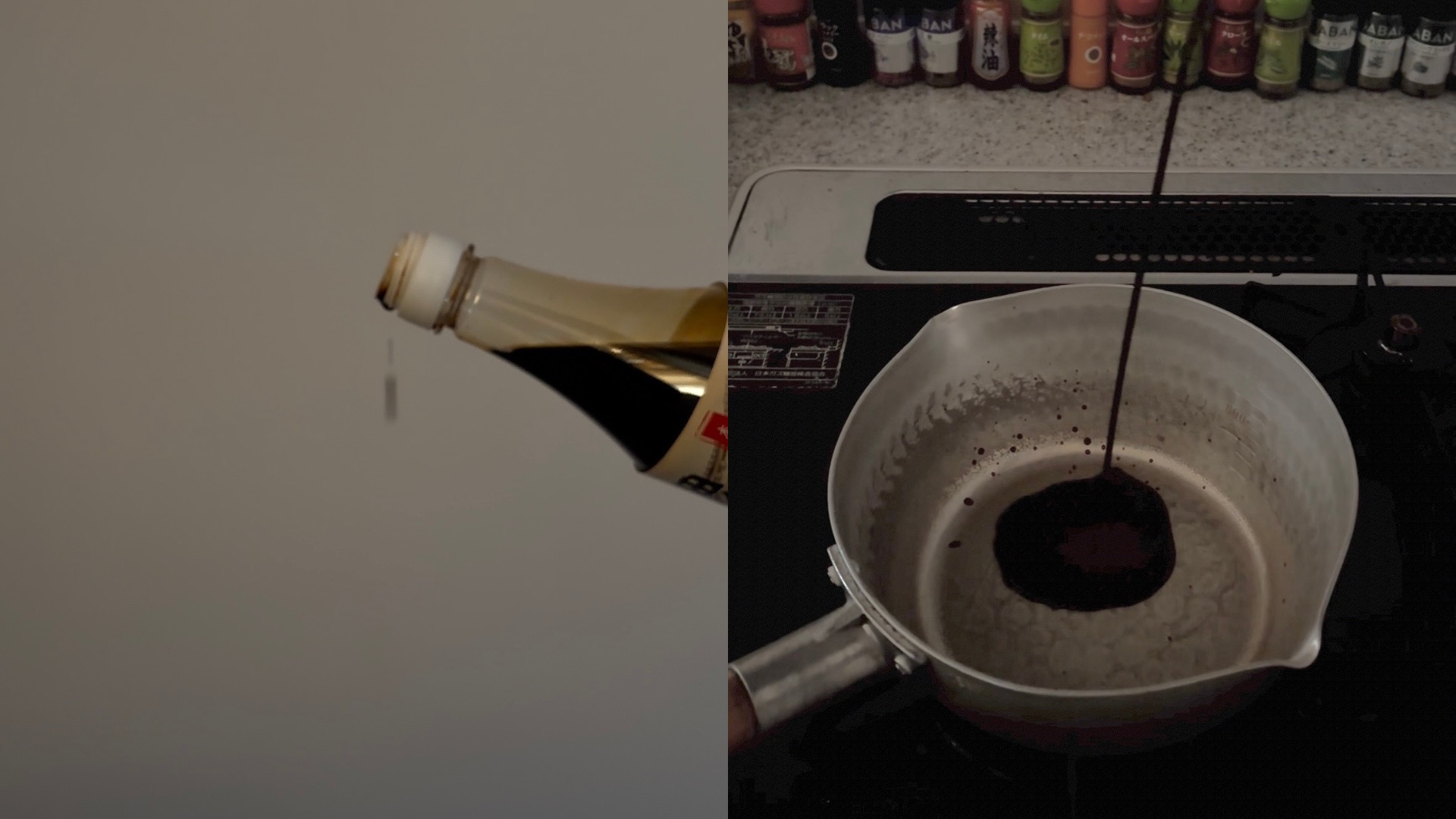

The Observation Setup: Raw vs Heated, Nothing Else Changed

To keep the observation clear, the setup was intentionally minimal.

- One type of soy sauce

- Same kitchen

- Same timing

- Same quantity

The only variable was heat.

One portion was used as-is (raw soy sauce).

Another portion was added during cooking (heated soy sauce).

No adjustments were made to compensate for flavor.

No attempts were made to “balance” the result.

This is not an experiment designed to prove a point.

It is an observation designed to reveal one.

The goal was not precision, but clarity

—making changes visible rather than measurable.

Observation One: Aroma Appears Before Flavor

The most noticeable difference was not how much aroma was present,

but where it appeared in the eating experience.

When used raw, the aroma arrived first.

Before the soy sauce touched the palate,

a scent rose through the nose—

distinct, expansive, and weighty.

The impression of umami, however, was relatively faint.

When heated, this sequence shifted.

The volatile, nose-passing aroma perceived

in the raw state no longer appeared at the front.

The heavier aroma also felt less pronounced.

Instead, warmth spread across the mouth first,

carrying umami with it.

A subtle aroma was present,

but it remained within the mouth rather than lifting outward.

Nothing was added or removed.

The soy sauce did not become weaker or stronger.

What changed was the order in which aroma and

flavor made themselves known.

Observation Two: Saltiness Is Felt in a Different Order

The difference in saltiness was not a matter of concentration, but of heating.

When used raw,

a sharp saltiness was perceived immediately upon contact.

It appeared at the very beginning of the experience,

before other sensations had time to unfold.

When heated,

this initial sharpness was no longer present.

The saltiness felt rounder,

emerging later and more gradually,

integrated with warmth and umami

rather than standing alone.

The salt content did not change.

Only how it felt.

The saltiness didn’t disappear like the aroma,

it was just muted by the heat.

Fermentation Is Not Always the Star

Fermented aromas are volatile and sensitive to heat.

They react quickly, not by disappearing, but by relocating.

Heating soy sauce does not destroy fermentation.

It draws it back.

Fermentation is often discussed as something to highlight:

more aroma, more character, more presence.

But fermentation does not always need to stand in front.

In Japanese cooking, there is a clear distinction between fermentation that leads and fermentation that supports.

Sometimes it speaks.

Sometimes it holds the structure quietly in place.

Both are intentional.

What This Means for Professionals

For chefs and food professionals, this observation challenges a common assumption:

Raw is not inherently superior.

Heated is not inherently compromised.

They are different design choices.

Soy sauce is not just a fermented product to select.

It is a fermented seasoning to deploy.

How it is introduced—when, where, and in what state—

changes its role within a dish.

Understanding this expands the vocabulary of

Japanese fermentation beyond recipes and rules,

and toward use, timing, and intention.

For those who want to experience these choices in practice,

immersive fermentation programs in Japan

offer a deeper context than recipes alone.

Soy Sauce Changes by Use, Not by Recipe

Nothing about the soy sauce itself changed.

The fermentation was already complete.

What changed was how it appeared—

and how it was received.

This is why Japanese fermentation is

often understood through practice rather than explanation.

Before it is named, it is used.

Before it is theorized, it is felt.

Sometimes, watching how something changes is

enough to understand why it matters.

Our newsletter explores Japanese fermentation

through observation, not instruction—

for those who want to learn how to notice.

No responses yet