Bonito flakes, or katsuobushi in Japanese, are one of the most iconic ingredients in Japanese cuisine. If you’ve ever seen paper-thin fish flakes “dancing” on top of takoyaki or tofu, you’ve witnessed the magic of dried bonito. But what exactly are bonito flakes? Why do they move? And how are they made?

Whether you’re a foodie, a chef, or planning a trip to Japan, this guide will introduce you to the world of bonito flakes—what they are, how they’re made, their rich history, and how to use them in authentic Japanese cooking.

What Are Bonito Flakes Made Of?

Bonito flakes are thin, dried shavings of fermented skipjack tuna (Katsuwonus pelamis), known in Japanese as katsuo. After steaming and smoking the fish multiple times, it’s dried until rock-hard, then shaved into flakes.

Bonito flakes fall under the broader category of katsuobushi dried bonito flakes, a staple in Japanese pantries. Traditional flakes are made through months of fermentation and drying, while mass-produced versions skip fermentation and are made quickly using machines. Both types are available, but their flavor and depth differ significantly.

For those looking for kosher options, bonito flakes kosher varieties do exist, but availability is limited.

Why Do Bonito Flakes Move?

One of the most common questions people ask is: why do bonito flakes move? It’s not because they’re alive!

Bonito flakes are extremely thin and light. When placed on hot food like rice, tofu, or okonomiyaki, the rising steam causes the flakes to curl and sway—creating the illusion that they’re dancing. The motion is purely a reaction to heat and moisture. In other words, the cells repeatedly expand and contract as they absorb moisture from the steam from hot food and return to their original state from a dry state.

This fascinating behavior has led many viral videos and search queries such as bonito flakes moving or why do bonito flakes move—especially from tourists visiting Japan for the first time.

The History of Bonito Flakes

The oldest written description of dashi is found in a cookbook included in Gunsho Ruiju, a collection of recipes from the Okusa school of Japanese cuisine that is said to have begun in the Muromachi period.

During the Edo period (1603–1868), the traditional method of fermenting and drying fish was perfected. In fact, authentic honkarebushi (true fermented bonito) is still made today using similar techniques. The process can take several months and requires skill and patience.

Some katsuobushi producers in Japan have been operating for generations, preserving not just the flavor but also the craftsmanship and spirit of traditional washoku cuisine.

The Umami Power of Bonito Flakes: Inosinic Acid

Umami is known as the fifth taste—distinct from sweet, sour, salty, and bitter. It’s often described as a savory, brothy, or meaty flavor that creates a long-lasting mouthfeel.

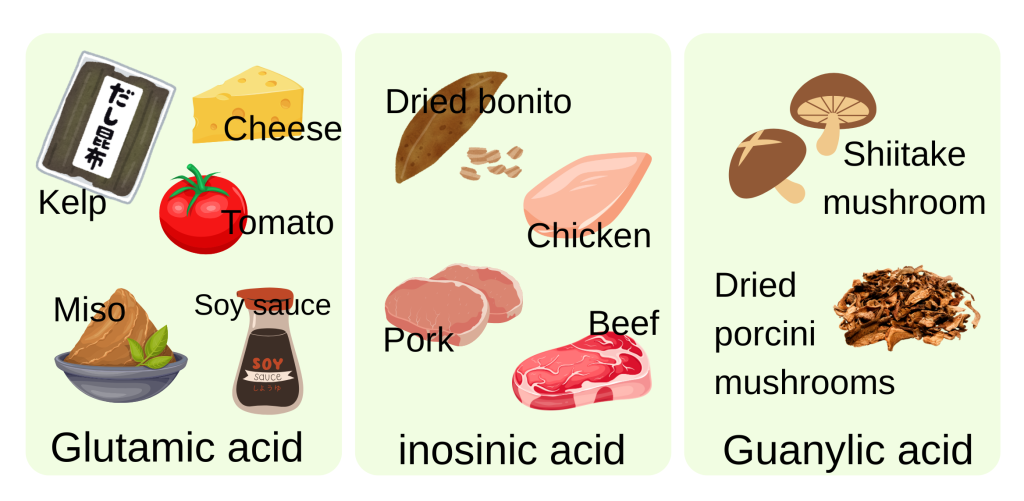

Bonito flakes are one of the most potent natural sources of inosinic acid, a key umami compound found in animal-based foods. When combined with glutamic acid from ingredients like kombu (kelp), the umami is amplified—a synergy called umami synergy.

This is why bonito flakes for dashi are so powerful in Japanese cooking. Dashi, the foundational broth in washoku, brings together these two umami sources for a deep, complex flavor.

How Bonito Flakes Are Made

Making traditional katsuobushi is a labor-intensive process:

- Boiling: The fish is gutted and boiled to remove moisture and bacteria.

- Smoking: It’s then smoked repeatedly (sometimes over 15 times) to dry and flavor the flesh.

- Fermentation: In premium versions, the smoked fillets are inoculated with mold, sun-dried and then repeatedly (up to six times) left to ferment for a total of several months.

- Drying: The final product is hard as wood and requires a special plane to shave.

- Shaving: The flakes are shaved to various thicknesses, depending on use—thin flakes for garnishing, thicker for stock.

Industrial products omit the processes of “Boiling,” ” Smoking,” and “Fermentation,” which results in lower costs but less depth of flavor.

This explains why discerning chefs and food lovers often look for buy bonito flakes online or search where to buy bonito flakes that are made using traditional methods.

How to Use Bonito Flakes in Japanese Cooking

Bonito flakes are incredibly versatile. Here are the most common uses:

- Dashi broth: The most traditional and essential use. Combine bonito flakes with kombu (kelp seaweed) to create the umami-rich stock used in miso soup, noodle broth, and more.

- Toppings: Sprinkle on tofu, okonomiyaki, takoyaki (octopus balls) etc.

- Seasoning: Mix into rice, pasta, or eggs for a subtle umami kick.

Can I Substitute Bonito Flakes?

If you’re vegetarian or can’t find katsuobushi, there are substitutes—though they won’t replicate the exact flavor:

- Shiitake mushrooms: Rich in glutamic acid, good for vegetarian dashi.

- Anchovy stock: Strong umami but saltier.

- Smoked fish: Can mimic the smokiness but lacks fermentation depth.

Searches like substitute for bonito flakes or bonito flakes substitute are popular among home cooks abroad trying to recreate Japanese dishes.

Where to Buy Bonito Flakes in US and Online

If you’re searching for bonito flakes near me in US, here are some options:

- Japanese or Asian supermarkets like Mitsuwa, or Nijiya.

- Whole Foods (limited selection).

- Online: Amazon, Japanese food specialty stores, and international groceries.

Look for keywords like “honkarebushi,” “smoked and fermented,” or “artisanal” to get high-quality flakes.

Why Bonito Flakes Represent the Heart of Washoku

Bonito flakes are more than just a garnish—they’re part of Japan’s cultural and culinary DNA. They embody the essence of umami, the respect for ingredients, and the deep tradition of Japanese cooking.

In 2013, UNESCO recognized washoku (traditional Japanese cuisine) as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. Dried bonito flakes are also related to one of the main reasons.

Learn More About Japanese Cuisine – Join Our Free Email

Want to explore more about authentic Japanese flavors? Join our free email and get:

- Basic knowledge about dashi, Japanese cuisine and health

- Special offers for cooking classes in Japan

- A chance to join our culinary exchange program and learn washoku firsthand

Whether you’re planning a trip to Japan or just love exploring global cuisine, we invite you to taste and learn the real Japan—starting with a single flake of katsuobushi.

Ready to take your washoku journey to the next level?

No responses yet